Organizations: Size & Time

This blog post was born out of a question I’ve asked myself. The question was “does it make sense for a multi-thousand people organization to have specific objectives for the next five years?”. My intuition says that the answer is a yes. It seems to make sense for a multi-thousand-person organization to have specific longer-term objectives. But I’m not a person satisfied with intuitive solutions. I’ve tried searching my mind for a fundamental answer. This blog post is the outcome of my search.

CEOs Don’t Steer

One article I love to reference on the topic I tackle in this blog post is the serious parody CEOs Don’t Steer by Venkatesh Rao:

CEOs are orientation locks. The opposite of steering is orientation locking - to enforce Newton’s first law, the inertia one, on dancing human systems inclined to violate it. Contrary to popular belief, it isn’t inertia that’s the problem for most companies. It is the lack of sufficient inertia in the right direction.

The title of the article is less subtle than the actual content. I’m not a fan of generalizations, so I wouldn’t like the treatise otherwise. There are, of course, situations when CEOs steer their companies. Big company CEOs maneuver less than the executives of smaller companies. Myself, I can name multiple significant steering decisions by various chief executives. Reed Hastings had made a successful steering decision when he reoriented Netflix by closing down their DVD business to focus entirely on streaming.

Orientation locking is the same as setting long-term objectives. A CEO sets the target for the company to achieve, and the organization goes off towards that target. To steer means to change target objectives.

CEO steering is an expensive proposition. It becomes more costly the larger organization becomes. Each time new company objectives are set, the whole organization has to reorient itself towards the new target. People have to grasp the new direction and agree among themselves on what they’ll have to work on to push themselves towards that direction. Netflix’s example is a potent one on the potentially extreme cost of steering: the whole business lines can be shut down, people change and lose their jobs.

Person

The extreme opposite of a big company is a single person. A single person can change direction more easily. The cost is still there, and the momentum is still lost. But it’s comparatively small. If I decide to change my personal objectives for this year, I can pretty much start gaining momentum towards the new objectives the next day.

These extreme examples help us start forming a model for how to think about setting direction. For a small number of people, the cost to change direction is smaller. For many people working together, the price paid to change direction is higher.

The cost translates into time. If the cost to change direction is high, the direction has to be set and held for the long term. A single person can still set the target for the long term. It’s helpful to figure out where you want to end up in 5 years and change your daily behaviors accordingly. But the big companies don’t have that choice. A big company can’t change direction every day; it’s too expensive.

Teams

Not to say that there isn’t value in changing direction. Quite the opposite. Each day we learn new information. We can use that information to reorient ourselves and our targets. This idea meshes well with how teams work in many technology companies.

Many software development teams worldwide work in one to four-week iterations (also called sprints). The basic idea is to develop a system through repeated cycles. Short iterations allow software developers to take advantage of what was learned during the development of earlier versions of the system.

The challenge for a larger software development organization is locking the high-level direction while maintaining team-level agility. While it’s not the focus of this article, how to set direction is also essential. When the direction becomes a set of detailed instructions, there’s a risk of losing the team-level agility.

Time & Number of People

I’ve established that a single person can change direction every day, while the leaders of big companies have to look towards the long-term. The next thing to figure out for our model is the relationship between time and the number of people in the organization.

The relationship can’t be linear. Think of it this way: we can change the direction for a single team of 10 people every couple of weeks. Then let’s say we’re ok with setting direction for six months in an imaginary 100 people organization that consists of 10 such teams. Then let’s say the organization grows to 1000 people. If the relationship were linear, that would mean setting direction for 4-5 years. Still ok. But if then the organization grows to 10000, we’re looking at 40-50 years, which doesn’t make sense. An organization of 10000 people can likely get away with planning for 4-5 years.

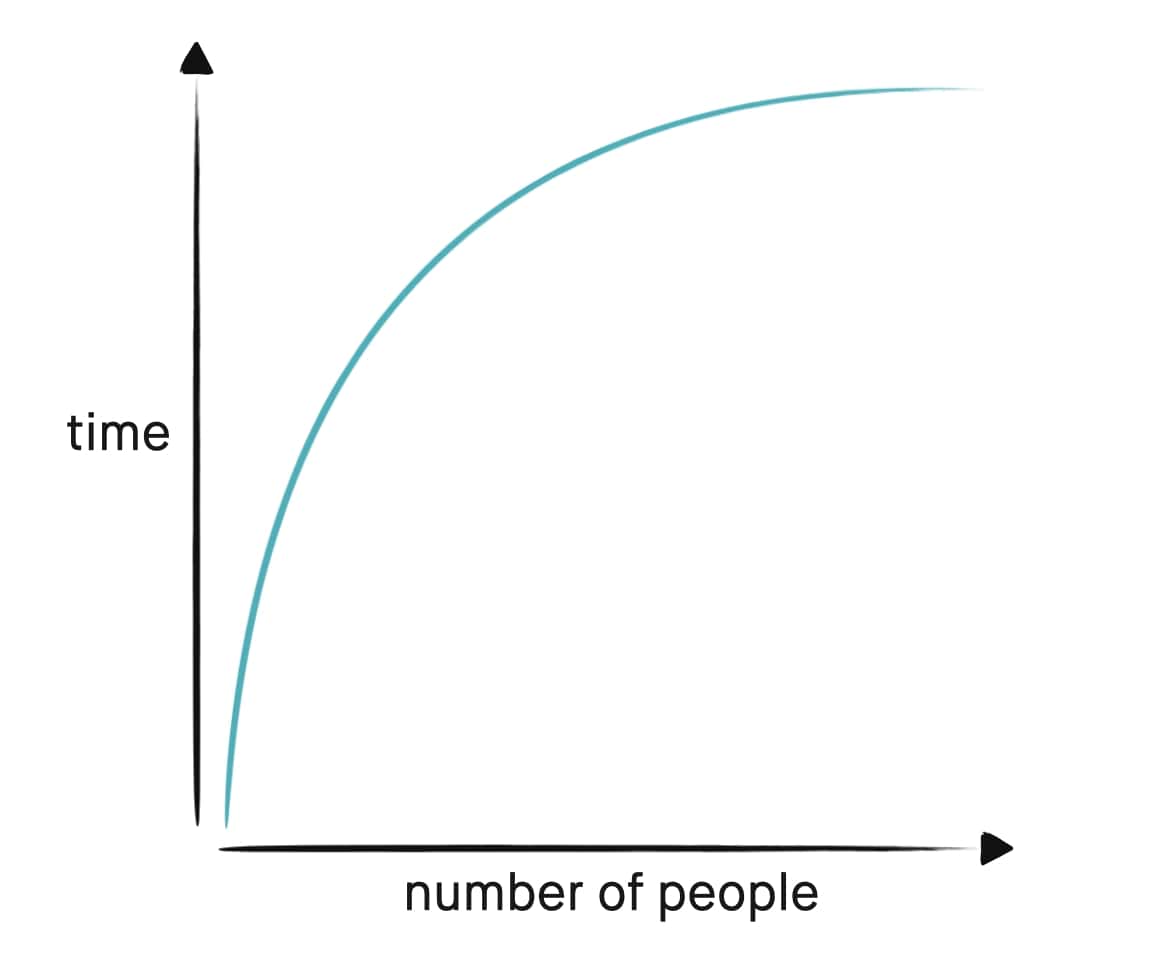

This suggest the relationship can be represented with a power curve:

Layers

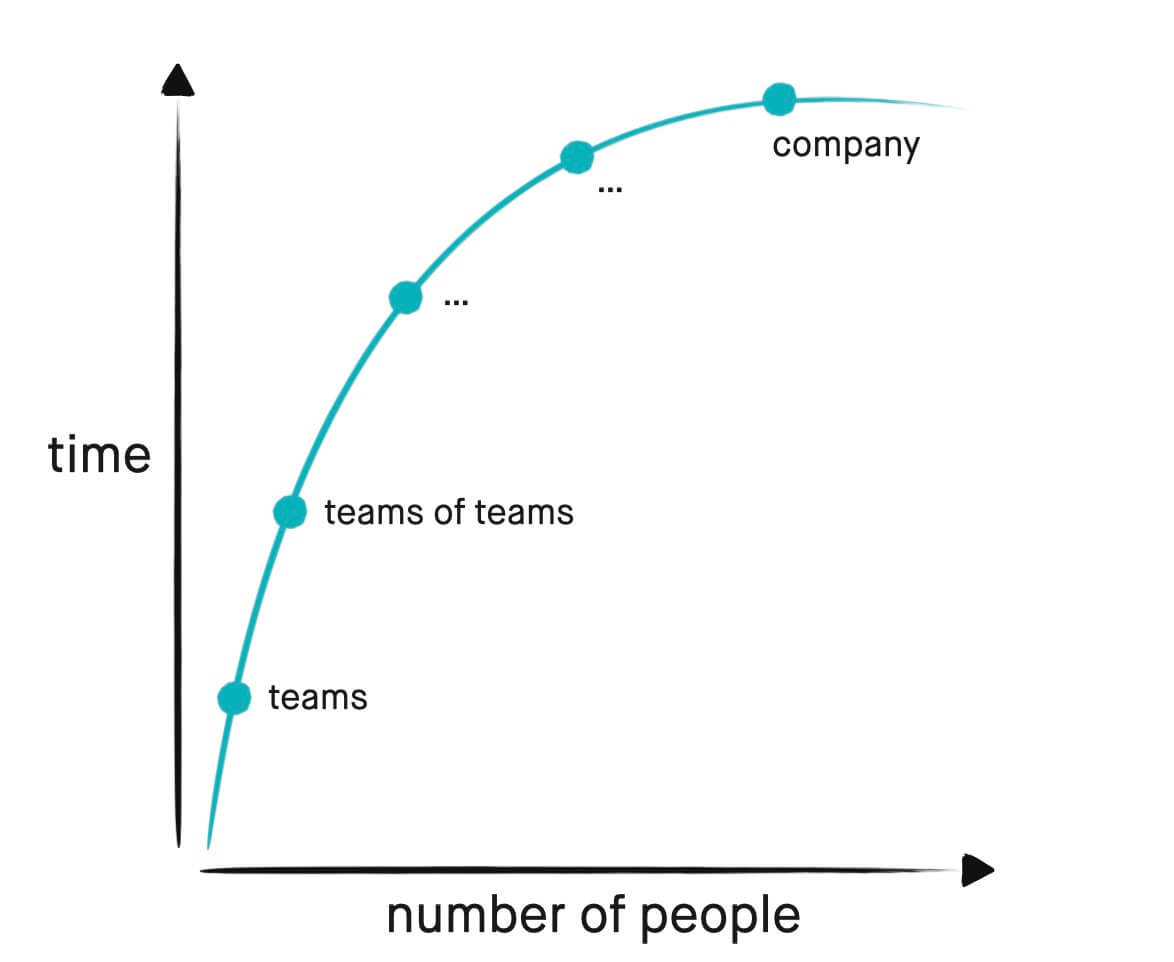

I’ve mainly focused on how different organizations will choose different time horizons. But the same is true for different layers (teams, teams of teams, the whole company) of a specific organization. Different layers of an organization will choose the right time horizons for that particular layer.

Not to say that each team in an organization will choose to lock their orientation for, let’s say, two weeks. Each group of people is different. Some teams might know precisely what needs to be delivered over the upcoming three months. Other teams will adjust every week based on new information.

With that in mind, generally, each layer of an organization will be further along the power curve:

Trade-offs

Each organization is different, and the curve’s steepness will be different. Suppose the organization operates in a highly-competitive new field, where there are a lot of opportunities to learn further information. In that case, it might want to maintain a 6-month direction, even when the organization grows into thousands of people. An organization in a more established field might want to set a 6-year direction. There is no perfect solution that applies to every organization.

Let’s go back to my original question: “does it make sense for a multi-thousand people organization to have specific objectives for the next five years?”. I have to conclude my search for an answer with an unsatisfying “it depends.” However, I have to mention that based on the power curve relationship, the answer will be yes for many multi-thousand people organizations.

Each leader has to consider the trade-off between the cost to change direction and the confidence of the “correct” path. It’s worth noting that this trade-off suggests that it’s beneficial for leaders to work with their teams to figure out and clarify the long-term direction. When the target is set, teams can operate efficiently and gain momentum towards their objectives. I agree with Venkatesh Rao when he writes that the lack of sufficient inertia in the right direction is more often the more significant challenge than the inertia itself.