To Escalate, or Not

To escalate, or not, that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

Escalations as a topic have been on my mind for some time now. In this blog post, I try to outline how I think about escalations and deduce when they are productive and when they are not.

Escalations

The word “escalate” has many meanings in various different contexts. In this blog post, the context is business and organizations. Escalating a problem means getting someone from the upper management involved to help solve the problem.

There are at least a couple of different versions of escalations possible in the workplace:

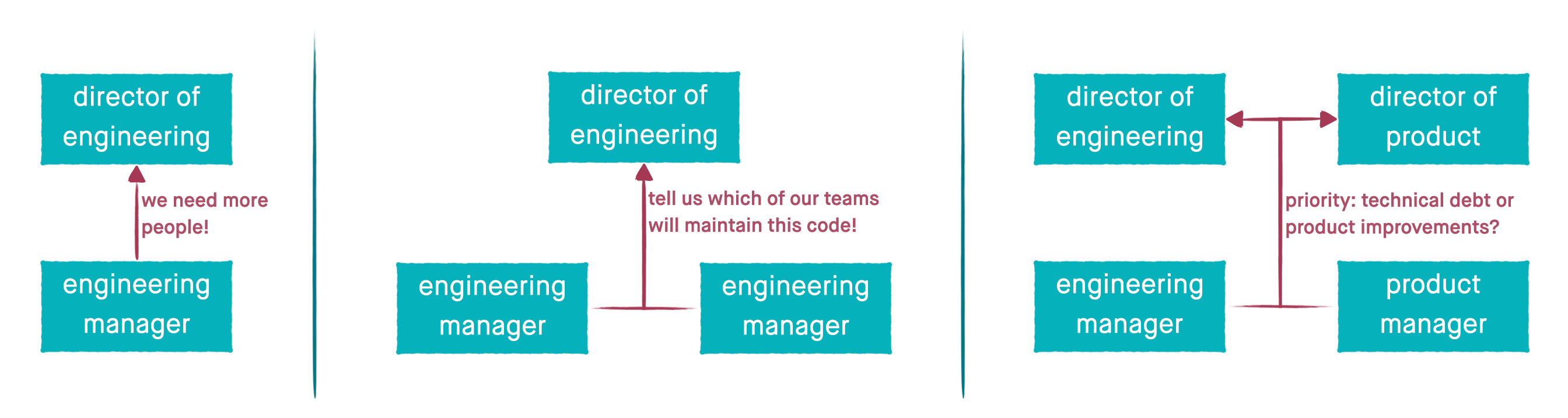

- A person cannot solve the problem themselves and asks for support from upper management. For example, the team cannot deliver everything that needs to be delivered, and the engineering manager asks the director of engineering for more staff.

- A person is in disagreement with another person, unable to resolve their dispute, they bring the issue to be decided by their manager. For example, two engineering managers disagree on which team should maintain a specific code module. They bring this disagreement to their director of engineering to resolve.

- A person is in disagreement with another person. They have different managers. Unable to resolve their dispute, they bring the issue to be decided by both of their managers. For example, engineering and product managers disagree on prioritizing work on technical debt or product improvements, bringing this disagreement to their directors.

(the wise director should definitely remind the engineering manager of the Brook’s Law and how adding more people might delay the project even longer)

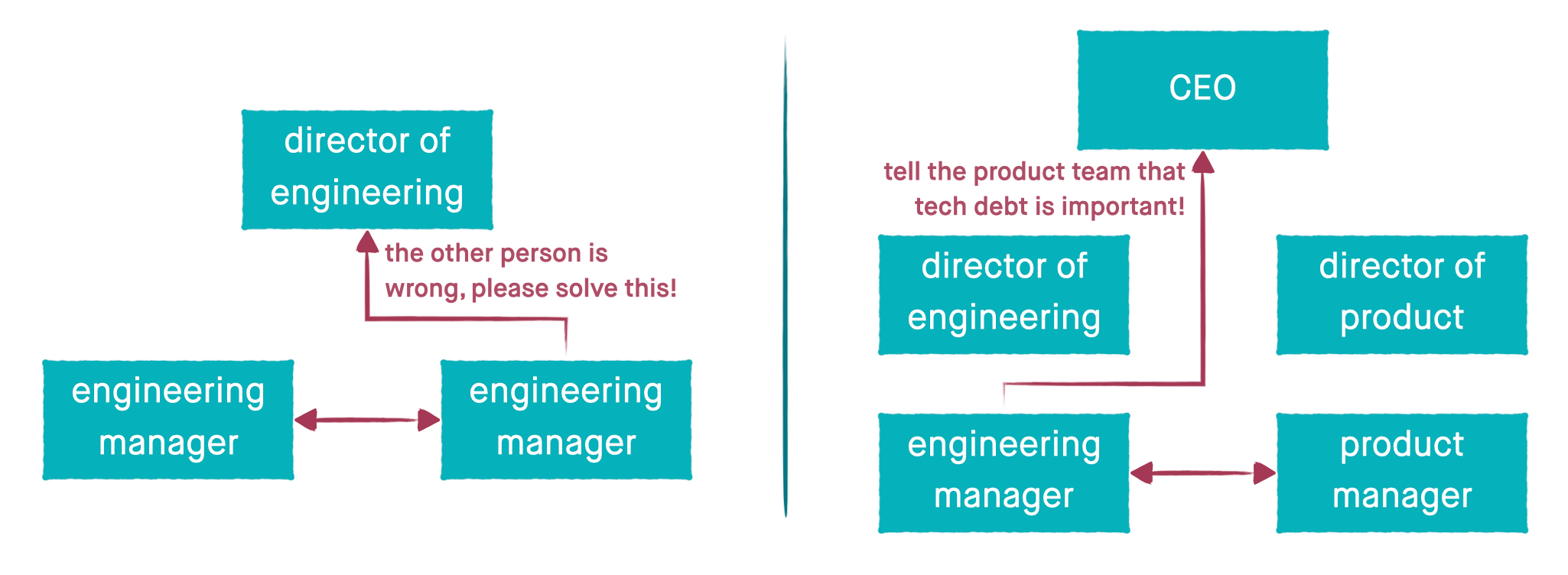

In the third example, the escalation could continue if the directors cannot agree. The escalations could potentially continue until they reach a single leader for both management lines, which could even be the CEO.

Clean Escalations

With the escalations defined, let’s go into what kind of escalations are productive. For the rest of the blog post, I’ll focus primarily on the disagreements between multiple people. While the example of the person needing support from their direct manager is also an escalation, it is not as interesting to explore further as the escalations involving multiple people.

Not everyone escalates productively. I’ve done my share of unproductive escalations. The most common example is telling the direct manager about the disagreement without informing the other person you will do that. It’s ok when looking for guidance. It’s not productive when expecting the direct manager to solve the issue. The direct manager then likely receives a skewed view of the situation and is also unable to do anything about the situation. Or worse, they try to resolve the situation with a skewed perspective.

I can imagine even worse examples of unproductive escalations. One example would be skipping your direct manager and escalating a disagreement straight to the CEO. It’s ok if the CEO doesn’t do anything about it. It’s incredibly unproductive if the CEO immediately decides to side with the person escalating the issue and informs everyone about their decision.

So, instead, what makes for an effective escalation? Clean escalations is an excellent pattern to follow. There are many articles on the web, so I won’t repeat them. The crucial part of this pattern is for both disagreeing people to come together to their manager (or managers) with a single document describing their disagreement and what they expect the manager to resolve. Enforcing this pattern removes most of the unproductive escalations. It forces people to understand the other side and clearly figure out the essence of the disagreement.

(and good news: in practice, figuring out what the disagreement is about and trying to document it solves some of the disagreements)

Writing a document together is not all it takes, of course. The escalation discussion afterward with the manager needs to be productive. The manager needs to understand the situation and create clarity with a decision. As someone who’s been the manager in those situations, I recognize it’s not always easy. In some cases, I can understand and sympathize with both sides of the argument. In those cases, I try to remember the cost of my indecision to the team and reason towards a principled model for my decision.

Fundamental Reason

Clean escalations seem like a lot of work. Some even see all escalations as unacceptable, disliking the idea of highlighting the inability to agree to their boss. Why do disagreements happen in an organization? Is there a way to prevent the need for escalations?

There are various reasons for escalations. Not all of them are productive. I’ll consciously limit the scope to escalations when people want to do the right thing and disagree on what is right. In my experience, that’s common anyway. I believe most people are good and have positive intentions.

One of the jobs of any leader is to create clarity. The clarity comes in many different forms. It answers various questions about the team. Why does the team exist at all? What behaviors are good? What are our goals? How should we go about achieving our goals?

(pizza or sushi?)

When people disagree, they disagree because something is not clear. The proactive way to prevent escalations is to create an abundance of clarity. If the engineering managers already knew which of the teams should maintain that piece of code, they wouldn’t need to escalate.

Proactively creating clarity requires effort. It’s impossible to create 100% clarity. Nor should it be the goal. Some things will be left unclear. The team should figure some things out themselves. Escalations are one way how managers find out about the need for more clarity.

Finding Balance

Imagine two extremes. One manager tells the team never to escalate the disagreements and that the team should always try to solve the disputes themselves. The other manager expects the disagreements to be escalated any time it takes longer than 5 minutes of discussion.

Both are clearly intuitively wrong. The team might get bogged in many unproductive discussions in the first scenario. In the second scenario, the team might not learn how to work together and is highly dependent on their manager. How to strike a balance to make the organizations productive?

The answer is a function of time. If the total time investment of two people resolving the disagreement is more than the total time investment of the manager getting involved, then the dispute should be escalated.

(you can make this more businessy by calculating salaries instead of total time investment)

There are some additional caveats to consider. In some cases, the disagreements carry a cost to the team if left unresolved. If the manager is on vacation that week, and the cost to the team is high, the team should likely persevere and try to resolve the disagreement themselves.

Practically, there is no need to estimate the total time investment. In most cases, the answer will be intuitively clear. People in a disagreement can usually gauge how far apart they are and whether they can realistically resolve the dispute within a reasonable time frame. Thus the guidance from the manager should be pretty simple: “if you can’t resolve the disagreement in a reasonable time frame, bring it to me.”

Summary

Escalations are a valuable tool for organizations to discover a lack of clarity and to create clarity. It’s an essential tool in the toolbox but easily misused. Escalating and doing so cleanly will increase clarity, create a swifter organization, and reduce the risk of damaged relationships.